- [host, Joe Hanson] They make their living by flipping homes, except once they've built or repaired a dwelling and they move on, they leave the whole community better off for having occupied it.

Of course, I'm referring to the beaver.

Our relationship with the beaver is, well, it's complicated.

But 400 or so years after humans skinned them to near extinction in the name of headwear, more and more scientists are starting to ask the question, could beaver be the ally we've been waiting for when it comes to saving the environment?

Beaver thrived in the United States and Canada for centuries.

It's estimated that as many as 400 million of them lived on the continent.

That breaks down to between 5 and 30 beaver for every kilometer of stream or river on the continent.

But as colonization took hold in the 16th century, trappers began to hunt them in earnest for their pelts and scent glands.

Then, one of the most ridiculous and regrettable fashion trends in human history nearly wiped them off the continent, the beaver hat.

Yeah, seriously.

Today, there are an estimated 10 to 15 million beaver left in North America.

In the meantime, people had started farming on former beaver land and they didn't want the beaver back.

Their solution?

Beaver relocation.

It's called translocation and it has a long-standing roots in this country.

In the 1940s, the Idaho Fish and Game Department made this film.

- [Film Narrator] Into the drop box, nearly ready for that flight back into the mountain.

The plane makes a careful approach, ready for the drop, now into the air, and down they swing.

- [Joe] Yeah, that is real.

They say hindsight is 2020, but someone had to think this was not a great vision at the time, right?

This is filmmaker, Sarah Koenigsberg, and that is her very good dog, Willow.

Sarah made the film, The Beaver Believers, a documentary about folks trying to save the beaver in part through translocation.

But what many scientists have found out in the ensuing years is that moving beaver doesn't guarantee that they'll stay where we put them.

And if they're released in an area that's too degraded, they might not have the food and water depth that they need to survive.

- [Sarah] It's not as simple as just picking up some beaver from somewhere where they're having a conflict with humans and then just plopping them down.

In some cases, that's still appropriate and successful, but the thinking has really evolved to recognize there are all these other areas where we humans can help them out so that they can move on their own.

In the years following The Beaver Believers, I got fully sucked into the beaver microcosm and it's quite literally taken over my entire life.

- [Joe] And that's what's brought us here to Central Oregon, just outside of the Painted Hills where Dr. Chris Jordan and a team of scientists have created a kind of revolutionary beaver laboratory.

- [Chris] We started working in Bridge Creek to make it more productive for fish.

- [Joe] And Dr. Jordan learned early on in his work on Bridge Creek, that where there were beaver, there were fish, specifically the salmon and trout they were working to protect.

But why?

Though they're the second largest rodent in the world behind the capybara, beaver have a lot of natural predators.

In the West, that means coyotes, wolves, bears, and mountain lions, to name a few.

- [Chris] The way they escape from those terrestrial predators is by being in water that's deep enough that they can hide.

If they're in a smaller stream, they need to make the deeper water.

And this is where the dams come in.

They block the flowing water to make it deeper.

- [Joe] And in doing so, they change the amount and the quality of water available in a stream system.

The small ponds that they build to escape predation are nurseries for juvenile fish.

Watching beaver gave the team a new idea for how people can restore river ecosystems.

- [Chris] And we call it low-tech process-based restoration.

And the low-tech comes from mimicking a beaver, no machinery.

We're enabling the natural systems to recover and rebuild themselves.

- [Joe] Instead of telling nature what to do, Dr. Jordan and his team are asking nature to guide them.

And if the environment needs fixing in order to put a stream where it wants to go, then they'll repair the land.

And that repair gives you some appreciation for just how hard industrious, little beaver work.

These are human-built beaver dam analogs.

- [Chris] So, these simple actions were meant to directly mimic the structures beaver built.

They were meant to trigger erosion and deposition processes.

- [Joe] Sometimes the beaver give the humans' work a beaver seal of approval, like this one, right here, a beaver dam analog that's become a real beaver dam.

- Oh, look, right here.

All this is fresh mud and fresh veg.

We're seeing more and more species that we care about really struggle due to habitat loss and beaver make habitat for all these other animals.

Something like 80% of all wildlife species depend on the kind of habitat that beaver create.

- [Joe] Beaver are mostly nocturnal.

They're also crepuscular, meaning they do work at twilight.

Basically they're staying out of the light to avoid their predators.

- [Sarah] So, if you go down to the confluence of the John Day River and Bridge Creek, it's just a very simple channel, it's curving along.

But if you start moving up through the restoration reaches, you kind of get a snapshot, step by step by step of the river returning to that beaver-dominated, really healthy and robust state.

- [Chris] The question remains, did we just get lucky?

Or is this actually an exportable, generalizable approach?

And so, we've tried it elsewhere and it works there too.

- [Emily] You can read about them written in trapper journals.

They're like, oh yeah, beavers totally fight fires.

That's great.

And then you go looking for the science on it and there's nothing there.

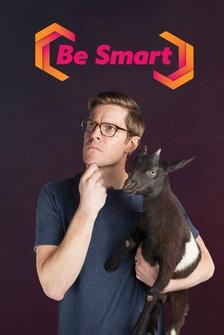

- [Joe] This is Dr. Emily Fairfax.

She's an ecohydrologist and remote sensing scientist.

Dr. Fairfax studies what happens to beaver landscapes during major disturbances like fires and droughts.

She's pretty good at stop-motion too.

Here's a film she made to show how beaver complexes fair in wildfires.

- [Emily] By building its dam, and then expanding that dam, and then digging these little canals out into the landscape, beavers are creating these really broad swaths of landscape that can resist all sorts of different disturbances.

So, when you have really similar streams with and without beavers, the streams without beavers burned three times more intensely than the streams that do have beavers.

- [Joe] To do her research, Dr. Fairfax looks at aerial images of rivers from different years to see how healthy the vegetation is, and then looks for differences between areas with and without beaver.

- [Emily] Beaver complexes stay very green.

What we have seen is that these beaver complexes, they're storing so much water in the pond and in the canals, and in the soil, that even when the droughts are going on for two or three or four years, there's enough water to keep the plants green.

It's like an underground irrigation system for the whole zone.

- [Chris] Beaver should be our national climate action plan because connected floodplains store water, store carbon, improve water quality, improve the resilience to wildfire, and what beaver do play an enormous role in controlling the dynamics of those systems.

So, yeah, it sounds really trite to give a national climate action plan to some rodents.

But if we don't do that directly, we should at least be trying to mimic what they do.

- [Emily] There's a lot of work that needs to be done for climate change.

Things are changing very quickly.

And even with all the money in the world, it's a hard problem to tackle.

So, why not let the beavers help us?

- [Sarah] You're not gonna find restoration practitioners who will literally work 24/7, 365 days a year.

Beaver just do it.

They'll help us, but we've screwed things up so badly that now they can't quite do it on their own, without us kind of setting the stage for them a little bit through restoration actions.

[light music] ♪