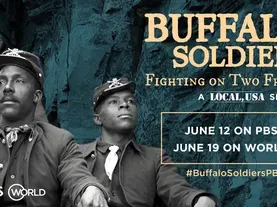

(men vocalizing) JERRY LAWSON: This story is about a group of soldiers that made up one segment of the United States Cavalry.

To the Indian, this soldier looked strange and different because he wasn't White.

He was Black.

Thick woolly hair, strong.

He sort of reminded the Indian of the great buffalo, so the Indian called this Black Cavalry soldier Buffalo Soldier.

♪ ♪ SHELTON JOHNSON: The Buffalo Soldiers were African American troops who were veterans of the Indian Wars.

Soldiers from the Deep South, these men sought refuge in the military.

DARRELL MILLNER: The example that the Buffalo Soldiers demonstrated was one that Black people were proud of.

LENARD HOWZE: One of the messages that I share with youth is that you have to figure out and learn where you come from.

They fought for us.

(fires) MILLNER: In the Jim Crow era, racial oppression was extreme.

JOHNSON: And a Black man standing tall could have been a dead man.

QUINTARD TAYLOR: But Native Americans don't necessarily see the Buffalo Soldiers as heroes.

JOHNSON: You don't ask when you are being enlisted, "Who am I gonna be fighting?"

♪ ♪ TAYLOR: They all came to the conclusion that if you fight for the country, you should be a full-fledged citizen.

That's what drove Buffalo Soldiers to fight even knowing that the United States might not honor that promise.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ MILLNER: In the narrative of American history, the West has always been this mythical and symbolic place in which heroic deeds were done.

And being capable of great deeds was not something that society was willing to admit that Black people were capable of doing.

And so, as a consequence, when we tell our stories, we leave the Black stories out, and the Buffalo Soldiers were a perfect example of that.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Perhaps the best example of this crossing-out of Black stories comes from the Spanish-American War, when the U.S. intervened in the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain.

(explosion echoes) The explosion of an American battleship, the U.S.S.

Maine, in Havana's harbor roused public support for war.

MILLNER: We go to war with Spain in 1898 to conquer Cuba and Puerto Rico, and eventually, that culminates in one of the most famous battles of American military history, the Battle at San Juan Hill.

NARRATOR: Black soldiers make up about 3,000 men, or 13% of the U.S. troops sent to Cuba.

♪ ♪ The Spanish-American War is brief, lasting roughly six months, but it was enough to promote the career of a little-known New York City politician named Theodore Roosevelt.

TAYLOR: Roosevelt was a prima donna.

He'd never been in the military before.

He literally organized the Rough Riders out of whole cloth despite the fact that he had no military background, and he sort of pushed his way in to lead the Rough Riders in Cuba.

ANTHONY POWELL: We've all heard the story of Teddy Roosevelt charging up San Juan Hill.

Now the real story.

They charged up San Juan Hill after the 10th Cavalry had breached the defenses.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: A Black soldier, Sergeant George Barry of the 10th Cavalry, planted the flags atop the hill.

Roosevelt and his men arrived well after the 10th and the 3rd Cavalry, a White regiment.

LOUIS BOWMAN (dramatized): If it had not been for the timely aid of the 10th Cavalry, the Rough Riders would have been exterminated.

Sergeant Louis Bowman, 10th Cavalry, "Tampa Morning Tribune."

After the battle was over, there are all the official photographs, and the photograph that we most see now in classrooms is Theodore Roosevelt standing in the middle and his Rough Riders all around him.

If you extend that photograph out, then you'll see the Black soldiers.

And in a way, that's a metaphor for what happened on San Juan Hill.

(chuckles) That it is assumed that Theodore Roosevelt led the Rough Riders up, they were the ones who defeated the Spanish, and that broke the back of Spanish resistance, and led to the American victory.

In fact, it was a victory that belonged as much to the Buffalo Soldiers.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The now little-known history of the Buffalo Soldiers stretches from what came to be known as the Indian Wars in the late 19th century through the end of racial segregation in the U.S. military following the Korean War.

The Buffalo Soldiers were all-Black cavalry and infantry regiments.

The first part of the Buffalo Soldiers' story takes place in the West, as the United States expanded into Indigenous lands.

This story is embodied by men like Ordnance Sergeant Moses Williams, a Medal of Honor recipient.

The second part of the Buffalo Soldiers' story picks up as Indigenous people are being forced onto reservations, and the United States begins engaging in military expeditions abroad in Cuba, the Philippines, and Mexico.

This story is embodied by Lieutenant Colonel Charles Young, one of the first Black graduates of West Point.

♪ ♪ MILLNER: In every American war-- the American Revolution, War of 1812, the Civil War-- all of those have included large involvements of African Americans.

(guns and cannons firing) NARRATOR: When the Civil War broke out in 1861, abolitionist Frederick Douglass lobbied the Lincoln Administration to accept Black men into the Union Army.

DOUGLASS (dramatized): Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letters "U.S.," let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pockets, and there is no power on Earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.

NARRATOR: Thousands of Black men were recruited by African American physician Martin Delany, who was commissioned as a major to lead the United States Colored Troops.

WOMEN: ♪ Glory, glory, hallelujah ♪ ♪ We are Colored Yankee soldiers ♪ ♪ Who've enlisted for the war ♪ ♪ We are fighting for Union ♪ ♪ We are fighting for the law ♪ NARRATOR: By the time the war ended in 1865, 40,000 African American soldiers had died to help keep the nation whole.

WOMEN: ♪ Glory, glory, hallelujah ♪ ♪ Glory, glory ♪ DELANY (dramatized): Do you know that if it was not for the Black men, this war never would have been brought to a close with success to the Union?

Major Martin R. Delany, 1865.

NARRATOR: President Lincoln agreed, saying, "Without the military help of the Black freedmen, the war against the South could not have been won."

At the end of the war, the United States Colored Troops were disbanded.

♪ ♪ Wartime casualties had reduced the U.S. Army to a fraction of its former size.

♪ ♪ RYAN BOOTH: It isn't until the end of the Civil War that the nation's energy shifts, and they're suddenly interested in Western land and expansion.

Manifest Destiny, extending America from shore to shore, from sea to sea, was kind of an official policy, but it was also an attitude.

Most people forget that we are on lands that once had all of this rich Native American life.

That there were people who were living and dying and being born on these lands.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In order for the quest for continental expansion to succeed, the Indigenous peoples who had lived on the land for thousands of years had to be dealt with.

BOOTH: They're building these railroads through Native homelands, which inevitably creates conflict.

NARRATOR: "Indian removal," as it came to be called, required a larger military force.

In 1866, Congress authorized the formation of 30 new units.

MILLNER: And that included two African American cavalry units and four African American infantry units.

POWELL: Many of the veterans of the United States Colored Troops, they would become the nucleus of the soldiers that enlisted in the six Black regiments after the Civil War.

The economic circumstances are what's driving things.

POWELL: For a young African American man, to go into the Army was all about making money.

JOHNSON: If you're poor, if you're a sharecropper's son, that $13 a month sounds pretty good.

MILLNER: You have to remember that although Blacks were now newly free-- slavery had been abolished by the adoption of the 13th Amendment-- their real condition in the American South had not changed that much.

They had no property, they had no money, they had no political power.

JOHNSON: They come from a background where it was illegal to teach an enslaved person to read or write.

If you tried to vote at that time, there were literacy tests that were there, put in front of you, and they were designed so that you would fail that test.

And if you could pass the literacy test, if you could pay for the poll tax, you had to deal with outright intimidation at the polling place.

All of these barriers were put in front of them, but which road was clear and open?

And that was the road to enlistment.

♪ ♪ POWELL: When I was a kid, I was very, very lucky to have my grandfather who had been a Buffalo Soldier.

His name was Samuel Nathanial Waller.

He joined the Army in 1887 and retired in 1927.

He died in 1979 at 105.

I asked him one time, I said, respectfully, "How come you served this racist country for 40 years?"

♪ ♪ And my grandfather told me something that it took me a while to appreciate.

He said the Army gave him the only part of the American Dream that the nation would let him share in.

♪ ♪ The Army offered to them something that outside of its structure didn't exist: an opportunity to advance, an opportunity to grow.

That is why many of them joined.

(people talking in background) NARRATOR: In October 1866, in Lake Providence, Louisiana, dozens of Black men show up to join the 9th Cavalry.

One of them is 21-year-old Moses Williams.

GREG SHINE: We don't know much about Moses Williams' family at all.

And what little information we have is from his enlistment papers over the years.

MOSES WILLIAMS (dramatized): Father and Mother died when I was an infant.

One brother died of consumption, one sister of fever.

Moses Williams.

NARRATOR: What he describes as "smallpox when I was 20 years old" left him with almost zero vision in his left eye, which makes his later reputation as a skilled marksman... (gun fires) ...extraordinary.

When Williams enlisted, he could not read or write.

Service in the Army gave Williams the opportunity to start educating himself.

The soldiers got meals, they got uniforms, they got pensions and benefits.

But at that time, Black soldiers could only rise as high as sergeant.

The ranks of lieutenant and above were held by White officers.

♪ ♪ In Missouri, another former slave chooses to enlist under the assumed name of William Cathay-- because she was female.

She was born Cathay Williams in Independence, Missouri, in September 1844.

MILLNER: There were few opportunities for aspiring young Black women in this time period beyond marriage, or beyond domestic service to White society.

NARRATOR: Once owned by a wealthy farmer, Cathay was liberated by the Union Army, but pressed into service as war contraband.

CATHAY WILLIAMS (dramatized): When the war broke out and the United States soldiers came to Jefferson City, they took me and the other Colored folk with them.

I did not want to go.

Colonel Benton wanted me to cook for the officers.

Cathay Williams, 1862.

NARRATOR: The 22-year-old had no experience as a cook, and was soon reassigned to the laundry, exploited by the Yankees as she had been by her former master.

After the war, used to the military life, she disguised herself as a man to enlist in the Regular Army near St. Louis, Missouri, on November 15, 1866.

CATHAY WILLIAMS (dramatized): I wanted to make my own living and not be dependent on relations or friends.

How she was able to get into the infantry, you know, during that time is to me still amazing.

NARRATOR: "William Cathay" passes a clearly superficial examination and is assigned to Company A of the 38th Infantry.

CATHAY WILLIAMS (dramatized): I carried my musket and did guard and other duties while in the Army.

NARRATOR: During her two years of service, Cathay Williams and her unit march roughly 1,000 miles on foot, from Fort Harker in Kansas to Fort Bayard in New Mexico Territory, enduring extreme weather, meager rations, and primitive living conditions.

The conditions in which they served was terrible.

You had so many soldiers dying, so many soldiers being disabled, because of cholera and different types of diseases.

NARRATOR: After several hospitalizations for rheumatism and neuralgia, Cathay's sex was finally discovered by an Army surgeon.

She was discharged on October 14, 1868.

CATHAY WILLIAMS (dramatized): The men all wanted to get rid of me after they found out I was a woman.

Some of them acted real bad to me.

NARRATOR: Upon her discharge, Cathay Williams discarded her male disguise and struck out for Colorado, where she worked as a cook and a laundress.

Stricken with diabetes and neuralgia, she applied for an Army pension, but was refused.

Cathay Williams died in Trinidad, Colorado, in 1893, at the age of 48.

Final resting place unknown.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Of the six new regiments of Black soldiers created in 1866, after the Civil War, two are ordered to Texas, one to New Mexico Territory, and the others to Kansas and the Indian Territories in present-day Oklahoma.

Only two are initially stationed outside the West.

Even those regiments would soon be posted to the frontier.

The American West was a very difficult, hostile place to live at this time, whether you were engaging in combat or not.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Mexican bandits and White outlaws operate freely on both sides of the Rio Grande.

And bands of Kiowa, Comanche, and Mescalero Apaches raid across West Texas.

SHINE: The Buffalo Soldiers served as a police force, because it was literally the Wild West.

NARRATOR: Moses Williams and the 9th Cavalry will spend the next decade in Texas.

They range out on patrol for as much as a year at a stretch.

But despite their role in securing the frontier, many Texas citizens do not welcome the Buffalo Soldiers.

Think of the irony here.

Black people were being attacked in East Texas by Ku Klux Klan types.

Black people in West Texas are defending Whites from Native Americans.

MILLNER: The Blacks who had to coexist in those Western outposts would be surrounded by former Confederates who would look upon a Black soldier as not a full human being, and would not be willing to treat a Black soldier the same way that they would treat a White soldier or a White citizen.

NARRATOR: When the 9th Cavalry first arrives in Texas, a White company commander, Lieutenant Edward Heyl, orders several of his men hung by their wrists from tree limbs when they did not respond quickly enough to his orders.

Heyl's brutality results in a mutiny.

Two officers are killed, and several of the soldiers are court-martialed and jailed.

Heyl gets off with a reprimand.

There's controversy about how the Buffalo Soldiers got the name "Buffalo Soldier."

SHINE: As early as 1872, soldiers' letters reference the term "Buffalo Soldiers."

FRANCES ROE (dramatized): The officers say that the Negroes make good soldiers and fight like fiends.

The Indians call them "Buffalo Soldiers," because their woolly heads are so much like the matted cushion that is between the horns of the buffalo.

JOHNSON: The Plains Indians, the Lakota, Dakota, Sioux, the Cheyenne, they saw these African American soldiers, and because of their ferocity in battle and the, the texture of their hair, they began to call them "Buffalo Soldiers" as a term of respect.

The buffalo were incredibly important.

They were at the heart of culture for these tribes along the Great Plains.

NARRATOR: Another possible explanation is that the name could have come from the heavy buffalo robes that soldiers wore in the winter.

But regardless of its origins, the name "Buffalo Soldiers" stuck.

MILLNER: And so it was the name that they adopted for themselves and held with honor well into the 20th century.

WOMEN: ♪ Buffalo soldiers ♪ NARRATOR: Soon after his enlistment, Moses Williams is promoted to first sergeant.

He would have been both an adviser to his commanding officers and a mentor to men of lower rank.

SHINE: The role of sergeant was key in an Army company.

The sergeant not only helps oversee the daily activities of those soldiers, but also is that conduit above to the White officers.

SINGERS: ♪ Buffalo soldiers ♪ - ♪ Well, well, well, well ♪ - ♪ Buffalo soldiers ♪ NARRATOR: On May 20th, 1870, Williams ordered one of his men, Sergeant Emanuel Stance, to pursue a group of Apaches near Fort McKavett.

STANCE (dramatized): I discovered a party of Indians, about 20 in number, making for a couple of government teams.

They evidently meant to capture the stock.

I immediately attacked them by charging them.

SINGER: ♪ How dignified, sanctified ♪ STANCE (dramatized): I set the Spencers to talking and whistling about their ears so lively that they broke off in confusion and fled for the hills.

Sergeant Emanuel Stance, 9th Cavalry.

NARRATOR: For his bravery in this engagement, Stance became the first Buffalo Soldier awarded the Medal of Honor.

♪ ♪ Life at a typical Army post in the West would have been a hub of activity.

♪ ♪ SHINE: The day-to-day work of African American soldiers was escorting supply wagons, helping string telegraph lines, helping protect parties that were surveying locations for railway lines.

Really, the work that they were doing was supporting the American infrastructure moving west of the Mississippi.

All this expansion into the American West is coming at the cost of displacing Native peoples and their life ways.

♪ ♪ Who's on the front line of that conflict?

It's largely the Buffalo Soldiers.

MILLNER: We look back and we see two populations of color, so we assume there would be some kind of potential alliance.

The Buffalo Soldiers did not look at the Native Americans and see another, in quotes, "Colored population."

They saw a designated enemy.

JOHNSON: You don't ask when you are being enlisted, "Who am I gonna be fighting?"

When it came time to do their duty, they would do what they were paid to do.

JOHNSON: They didn't join to kill Indians.

They joined because it gave them a sense of respect to wear the uniform of the United States, to potentially sacrifice their life for the United States in the hope that that sacrifice would result in conditions improving for their loved ones back home.

BOOTH: On the one hand, it is a story of great triumph, but it's also a story about people being dispossessed.

It's a story about violence.

Part of the legacy of the Indian Wars is one of total war.

The U.S. Army attempted, in its own way, to starve, kill, maim, do whatever they could to be able to get the end that they wanted.

JACOB WILKS (dramatized): We destroyed everything in their village.

We found a vast amount of buffalo robes, of which each man made a choice of the best.

The rest we destroyed.

Their tents were made of poles over which hides were stretched, and these were all burned.

Sergeant Jacob Wilks, 9th Cavalry, 1874.

NARRATOR: After a decade in Texas, Moses Williams and the 9th Cavalry are ordered to New Mexico Territory.

The Buffalo Soldiers set out to track down a group of Apaches led by the charismatic warrior Victorio.

BOOTH: Victorio is probably one of the most brilliant tacticians of the war.

And so he does this hit and run campaign across the American Southwest and into Mexico.

NARRATOR: The 9th Cavalry pursues Victorio for more than a year.

In 1880, the 10th Cavalry joins in the chase.

U.S. and Mexican officials want to see the Apaches crushed.

NARRATOR: The Mexican army finally catches up with Victorio at Tres Castillos.

BOOTH: He ends up being pursued like a dog.

Ends up dying to try to achieve freedom for his own people.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Forty of Victorio's followers escaped, including a respected elder known to his people as Kas-Tziden and to outsiders as Nana.

He was 75 years old and crippled in one leg.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: On August 16th, 1881, I Company of the 9th Cavalry-- where Moses Williams served as First Sergeant-- came into contact with Nana's band in northern New Mexico.

It would prove to be a pivotal day in Williams' life and career.

Williams' commanding officer was Lieutenant George Burnett, a recent West Point graduate without much field experience.

So you really have him looking toward Moses Williams for support and leadership.

NARRATOR: Burnett describes Williams and Private Augustus Walley as "the two men who are always by me in every danger."

Burnett later recalled the events of that day.

BURNETT (dramatized): It was practically a running fight which continued for several hours, and we had driven the Indians eight to ten miles into the foothills of the Cuchillo Negro Mountains when they made a final and determined stand.

NARRATOR: As they attempt to cut off an Apache retreat into the mountains, Sergeant Williams spots a potential ambush, an Apache warrior in hiding.

♪ ♪ When Lieutenant Burnett dismounts and fires, warriors start shooting from the ridge.

SHINE: The commanding lieutenant's horse takes off and flees to the rear.

BURNETT (dramatized): Someone started the cry, "They got the lieutenant, they got the lieutenant!"

And with this, the whole outfit proceeded to follow suit.

I called to Sergeant Williams to go after them and bring 'em back.

SHINE: Moses Williams goes back to rally these soldiers and brought them back up to the line.

NARRATOR: As they charge back into battle, Burnett realizes that three privates had become stranded.

BURNETT (dramatized): My attention was attracted by one of the men calling to me, "Lieutenant, please, for God's sake, don't leave us!

Our lives depend on you!"

Private Walley mounted and galloped to him, while myself and Sergeant Williams were exposed to the fire of at least 25 or 30 Indians without the slightest shelter whatsoever.

(fires) SHINE: Moses Williams, Augustus Walley, and their commanding officer bring these soldiers that are abandoned to safety in great peril and almost the cost of their own lives.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: While Moses Williams battled in the Indian Wars, the first generation of Black cadets fought discrimination at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

One of those first cadets was Charles Young.

Born into slavery in Kentucky, Young's parents fled with their infant son Charles to Ohio, and freedom, in 1864.

Young's mother, Arminta, was one of the rare enslaved people who had found a way to educate herself.

BRIAN SHELLUM: And really was somebody that passed on to Charles Young the importance of education and what an education could do for a Black person.

NARRATOR: Soon after their arrival in Ohio, Young's father, Gabriel, joined the 5th Colored Heavy Artillery and served for a year in the Civil War.

SHELLUM: He loved the Army and he loved what it did for him.

And he passed that on to his son Charles.

It was one of the major reasons why Charles Young went to West Point.

NARRATOR: Young is admitted to West Point in 1884.

SHELLUM: 130 years ago, when Young attended West Point, it was a very difficult place.

It was a place that reflected the Jim Crow norms of society at the time.

MILLNER: Between 1870 and 1900, 12 Blacks had been admitted to West Point.

But because of almost unimaginable harassment and discrimination, nine of the Blacks were forced to leave before they graduated.

POWELL: They had been harassed by other cadets.

Johnson Whittaker was one.

He was tied up and he was cut.

And they didn't court-martial the, the cadets that did that.

They court-martialed him because they said he was lying, and he was dismissed from the academy.

NARRATOR: While at West Point, Young has to learn how to navigate a color line with the other White cadets.

SHELLUM: It was harder for him because he was Black.

What he learned from his struggles at West Point were lessons that he used later in life in the officer corps.

JOHNSON: His experience at West Point was so intense, so severe, he once said the worst thing he could ever wish on an enemy would be to make them a cadet at West Point.

SHELLUM: Young was the third Black graduate of West Point, in 1889, and he was the last Black graduate until 1936, a period of almost 50 years.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Enlisted men like Moses Williams did not get a formal education like the kind Charles Young received at West Point.

But the Army needed skilled clerks, and assigned its regimental chaplains to attend to the soldiers' spiritual and educational needs.

SHINE: Educational opportunities were really limited for African American men at the time, and so the Army offered this opportunity.

NARRATOR: With the encouragement of his regimental chaplain, Williams studies to become an ordnance sergeant, the officer in charge of arms and ammunition at an Army post.

SHINE: Ordnance sergeants were not appointed lightly.

It required appointment by the Secretary of War after recommendation from a board of officers.

NARRATOR: Williams passes the test and becomes one of the first Black ordnance sergeants in 1886.

He then transfers to the 25th Infantry to take charge of the ordnance at Fort Buford in the Dakota Territory.

It was a remarkable achievement for a man who could not read or write when he joined the Army.

♪ ♪ Three years later, in 1889, Charles Young graduates from West Point.

The racial barriers that he had overcome as a cadet would shape the rest of his career.

SHELLUM: The Army was preoccupied with minimizing Young's contact with White troops and White officers.

This meant that when he graduated from West Point, the Army had one choice: assign Charles Young to one of the four Black regiments.

NARRATOR: Lieutenant Young is assigned to the 9th Cavalry, Moses Williams' old unit, and posted to Fort Robinson, Nebraska.

SHELLUM: The mission of the Army had changed on the Western frontier.

NARRATOR: America's campaign to usurp Indigenous lands was almost finished.

Indigenous peoples had been forced onto reservations, like the Sioux reservation north of Fort Robinson, and the U.S. Army was tasked with making sure they didn't leave.

SHELLUM: And these larger posts like Fort Robinson were connected by railroad, by telegraph.

The posts just weren't isolated like they had been in the, in the former frontier time.

NARRATOR: But it was a lonely life for Young as a Black officer.

SHELLUM: As an example, say there was a mandatory function at the officers' club.

Charles Young would show up, stay for what he felt was an appropriate time, and excuse himself.

He had to stay on his side of the color line.

JOHNSON: Corporals or privates that were well beneath his rank would not necessarily salute him because that meant saluting him, a Colored man, and Euro Americans at that time did not show deference to any African American.

NARRATOR: In 1894, the Army reassigns Lieutenant Young to Wilberforce University in Ohio.

SHELLUM: His mission was to establish a military training program for Black officers, the first one in the country, at Wilberforce University.

NARRATOR: Unlike his experience of social isolation in the West, at Wilberforce, Young quickly becomes accepted as part of a vibrant Black intelligentsia.

SHELLUM: He developed a friendship with W.E.B.

DuBois, who was assigned as a professor at Wilberforce University at the time.

DuBois' biographer calls it the first genuine male friendship that DuBois ever had in his life.

NARRATOR: Young is also reunited with his mother, Arminta.

He purchases a house for his family that he calls Youngsholm, which would remain a refuge for the rest of his life.

In 1895, Moses Williams' final posting is to Fort Stevens, Oregon, where the Columbia River meets the Pacific Ocean.

The old Civil War fort is being modernized, and he is the only soldier still stationed there.

With no soldiers to command, Williams has one last battle to fight: the battle for recognition.

During the summer of 1896, he receives news that galvanizes him into action.

SHINE: Through his correspondence, he learns that at least one of his former fellow soldiers has received the Medal of Honor, and he realizes, well, he was in the very same action.

NARRATOR: Private Augustus Walley and Lieutenant George Burnett had both been decorated with the nation's highest military award for their bravery during the Battle of the Cuchillo Negro Mountains.

SHINE: At the time, the way that the Medal of Honor process worked, a soldier could self-nominate, provided that they had the support of their commanding officer.

Moses Williams tracks down his commanding officer, who had since retired and was living in Germany, who writes a very descriptive letter.

BURNETT (dramatized): I recommend Sergeant Moses Williams for a Medal of Honor for his coolness, bravery, and unflinching devotion to duty in standing by me in an open exposed position under heavy fire, thus enabling me to undoubtedly save the lives of at least three of our men.

NARRATOR: On November 23rd, 1896, the War Department responded.

MAN (dramatized): I am instructed by the Assistant Secretary of War to transmit to you the accompanying Medal of Honor, awarded to you by the president of the United States for most distinguished gallantry in action with hostile Indians in the foothills of the Cuchillo Negro Mountains.

NARRATOR: Moses Williams retires in May 1898 after 37 years of military service.

He moves to Fort Vancouver in Washington.

MILLNER: The unfortunate reality for many Buffalo Soldiers was that in spite of the kind of service that they provided, their fate after their military service was generally disastrous.

They did not receive high pay in the military.

They were not able to take advantage of opportunities that might have been available to them as civilians.

So, as a consequence, once many of their military careers were over, they were in very desperate circumstances.

That was the case for Moses Williams.

NARRATOR: Moses Williams dies a year later, on August 23rd, 1899.

He was buried with his sharpshooter's badge at the Vancouver Barracks Post Cemetery.

♪ ♪ When war breaks out with Spain in April 1898, Charles Young is stationed at Wilberforce University.

SHELLUM: The War Department wanted officers to stay at their posts to train the force, in case it was a longer war.

NARRATOR: But the war is over by July.

SHELLUM: So Young wasn't able to rejoin the 9th Cavalry to take part in the actions in Cuba.

NARRATOR: He doesn't get to witness the charge of the 10th Cavalry-- followed by Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders-- on San Juan Hill.

SHELLUM: During the Spanish-American War, the United States invaded the Philippine islands.

We took Puerto Rico, we took Cuba, we took Guam.

SHELLUM: It was a time when the president, the politicians thought, "Well this is our chance to establish an empire."

And so that led to the next war in the Philippine war.

NARRATOR: Philippine leader Aguinaldo and his revolutionaries had fought alongside the United States against Spain.

They now found themselves the possession of a new colonial master.

SHELLUM: The Filipinos were not happy.

They wanted their own freedom and they wanted independence.

SHINE: And so you see that war quickly turning to what's perceived by the Filipinos as a war against the United States.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: African Americans were divided in response to the U.S. war in the Philippines.

Ida B.

Wells argued that... WELLS (dramatized): Negroes should oppose expansion until the government is able to protect Negroes at home.

NARRATOR: Booker T. Washington agreed.

WASHINGTON (dramatized): The Philippine islands should be given a chance to govern themselves.

Until our nation has settled the Indian and Negro problems, I do not think we have the right to assume more social problems.

NARRATOR: But an editorial in a Black-owned newspaper, the Indianapolis "Freeman," supported the war.

MAN (dramatized): The Negroes must be taught that the enemy of the country is a common enemy, and that the color of the face has nothing to do with it.

NARRATOR: The debate among African Americans in the U.S. carried over to Black soldiers on the battlefield.

Filipino insurgents distributed pamphlets addressed to "the Colored American soldier" encouraging them to desert-- and a small number defected.

POWELL: Soldiers like David Fagan decided enough was enough, deserted, and they fought alongside Filipinos against their brethren.

Now they lost the war and they lost their lives.

But they did something that is purely an American principle: liberty and freedom.

That's why they deserted.

And I think that is misunderstood by a lot of people because they, as Black men, knew how America treated them at home.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Charles Young and I Company of the 9th Cavalry arrive in the Philippines on May 16th, 1901.

Newly promoted to captain, Young's first mission is to lead the Buffalo Soldiers up the Gandara River to pacify a village called Blanca Aurora.

SHELLUM: Young set off with I Troop.

They were in three flatboats being pulled by an armed gunboat.

NARRATOR: One of Captain Young's officers, Sergeant H.W.

Nicholas, described the mission in a letter.

NICHOLAS (dramatized): We were about 12 days going the 18 miles, off and on the boats, fighting our way up the stream on both sides of the river.

They would fight off one ambush, get back on the boats.

Tide would go in and out, and they'd be left high and dry because the Gandara River was a tidal river.

NARRATOR: Drawing close to Blanca Aurora, Sergeant Nicholas is stranded on a reef with the supply boats.

NICHOLAS (dramatized): The insurgents, seeing my unfortunate position, began to pour fire at us.

(guns firing) I had only six men with rifles.

We fought back with all the courage we had in us.

NARRATOR: Captain Young had the main body of his force divided on each side of the river, fighting his way forward.

NICHOLAS (dramatized): Upon hearing my volley firing, he knew that I had been attacked from the rear.

He rushed back to my aid and rescue, drove off the attackers, and, after the tide came in, we advanced cautiously along, arriving at Blanca Aurora.

NARRATOR: Previous missions to Blanca Aurora had failed, and many U.S. commanders resorted to scorched-earth tactics in their fight against the Filipino guerrillas.

Charles Young understood guerrilla warfare.

He pacified the village peacefully.

He gave them security and supplies, kind of separated them from the insurgents.

NARRATOR: Young's deft touch was so successful that his commanding officer promised I Company a plum assignment after the war.

SHELLUM: So they got duty in the beautiful city of San Francisco as a reward for their good service in the Philippines.

NARRATOR: Charles Young and I Company serve for another year in the Philippines and fight in the decisive Batangas campaign against General Malvar.

The Filipinos will not achieve their independence for another 44 years.

In 1903, shortly after Charles Young and I Company returned to the United States, President Roosevelt visited San Francisco.

SHELLUM: San Francisco planned a big parade down Market Street, and Young was selected to lead two troops of the 9th Cavalry as the honor guard for the president.

NARRATOR: It was the first time that Black troops had been included in a presidential honor guard.

SHELLUM: There were some troopers in the 9th Cavalry at the time who had charged up San Juan Hill with Teddy Roosevelt, so he knew them well.

NARRATOR: After Roosevelt's visit, Young and two companies of the 9th Cavalry are dispatched to Sequoia National Park.

POWELL: Charles Young was the first African American superintendent of a national park, and that was Sequoia National Park.

NARRATOR: Sequoia had only been established in 1890.

In the fledgling days of the National Park System, U.S. Army troops served as park rangers.

POWELL: They would send troops to the various national parks to make sure that people didn't homestead or people were not poaching.

JOHNSON: Charles Young has many accomplishments.

Building the first road to the top of Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the United States, that's incredibly significant.

But under his supervision, the first usable wagon road into Sequoia's Giant Forest was completed, and more work was done in the summer of 1903 than all the other preceding years combined.

NARRATOR: During that summer in Sequoia, Young begins courting Ada Mills, whom he soon marries in a small, private ceremony.

♪ ♪ SHELLUM: Ada Young brought some stability to the life of a bachelor.

Young was 40 years old at the time, she was 24, but she was well educated.

She was a good match for Charles Young.

NARRATOR: Officers like Captain Young had long been allowed to bring their wives to postings.

Starting in the late 19th century, enlisted men could bring their families, too.

TAYLOR: And so there now are communities that develop around these Buffalo Soldier outposts.

NARRATOR: The Buffalo Soldiers were often some of the first Black people in predominantly White settlements.

This created the opportunity for connection across communities.

As Charles Young argued in an impassioned speech in 1903... CHARLES YOUNG (dramatized): We are part and parcel of the body politic of the United States.

All we ask is a White man's chance.

Will you give it?

NARRATOR: Perhaps the most notorious incident of racial injustice involving the Buffalo Soldiers occurred in the summer of 1906, when the First Battalion of the 25th Infantry transferred to Brownsville, Texas.

On the night of August 13th, shots rang out and a White bartender was killed.

Locals claim that they witnessed Black soldiers firing weapons.

White officers attested that the soldiers had been in the barracks and none of their weapons had been fired.

TAYLOR: But because they were Black, they were all going to pay.

POWELL: 167 African American soldiers were discharged without honor for a crime that they didn't do.

QUINTARD: Many of those soldiers had served with distinction for 20 years.

NARRATOR: One of those soldiers was First Sergeant Mingo Sanders, who was partially blinded during his service in Cuba, and whose commanding officer called Sanders "the best non-commissioned officer I have ever known."

POWELL: It was Theodore Roosevelt who ordered this 25th Infantry discharged after the Brownsville affair.

NARRATOR: The African American community, which had supported Republicans since the Civil War, was outraged, but Roosevelt refused to budge.

POWELL: All of the evidence showed that these men were innocent, but because Roosevelt wanted to make sure that his Southern, you know, constituency was okay, that's what he did to those men.

NARRATOR: Charles Young faced a more subtle form of discrimination as a Black officer in a White officer corps.

SHELLUM: The Army was preoccupied with keeping Young in what they felt were appropriate assignments for a Black officer.

As Charles Young rose in rank to captain, major, this became an increasing problem.

NARRATOR: In 1904, the Army solved this problem by assigning Captain Young as military attaché to Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

He served for three years, gathering intelligence to help the U.S. plan for a possible military intervention on the island.

By 1912, the Army had assigned Young as military attaché to Liberia, a West African country founded in 1822 by free and formerly enslaved Black Americans.

The descendants of these founders called themselves Americo-Liberians, and ruled over a large Indigenous population.

SHELLUM: Can you imagine, in 1912, you're a Black man and you're going back to Africa, and he finds this upside-down world where former African Americans have gone and they've kind of reproduced plantations, and they're treating their own Indigenous people terribly-- as slaves, practically.

NARRATOR: Young's mission was to train the Liberian Frontier Force, which was drawn from the Indigenous people.

He was assisted by three other Black U.S. Army officers.

SHELLUM: At first, he was all behind the mission.

But over the three years he was there, he began to doubt the motives of the Americo-Liberians who were trying to suppress the Indigenous people.

NARRATOR: Liberia in 1912 was a dangerous place for Westerners.

SHELLUM: Bad food, bad water.

There was one U.S.-trained doctor in the whole country.

NARRATOR: Young had brought his wife, Ada, and their two young children to the post, but they had to be evacuated due to the lack of safe water and food.

Young develops blackwater fever, a malignant form of malaria, which will come back to haunt him later in life.

In 1916, Charles Young and the Buffalo Soldiers fight in the last great cavalry campaign in the West.

MILLNER: Pancho Villa was a warlord in Northern Mexico at the turn of the 20th century.

And our relationship with our southern neighbor was probably even more tumultuous than the one we're experiencing in this generation.

NARRATOR: Villa's bandits raided Columbus, New Mexico, and shot up the town, killing 18 Americans.

SHELLUM: And the United States was not happy about that.

MILLNER: And so they sent an expedition that at its height reached 10,000 American soldiers into Northern Mexico.

NARRATOR: Charles Young had been promoted to major while stationed in Liberia.

The Army transfers Major Young to the 10th Cavalry to serve under General Jack Pershing in the Punitive Expedition.

Early in the expedition, on April 1st, 1916, Major Young and the 10th Cavalry surprise a group of 150 Villistas near the outskirts of Agua Caliente.

SHELLUM: Young had three cavalry troops and a machine gun troop.

NARRATOR: The troopers of the 10th Cavalry dismount and attack, forcing the Villistas to retreat behind a ridge.

SHELLUM: So Young used the machine gun troop as covering fire to pin down the enemy force, and he just overwhelmed them.

NARRATOR: Under covering fire from the machine gun troop, Young directs a flanking maneuver, forcing the Villistas to retreat in disorder.

Young then leads a pursuit of the Villistas in a running battle until his men and horses are overcome by exhaustion.

♪ ♪ It's the first time that I know of that Americans used machine guns in covering fire, and it caught the eye of General Pershing.

(cannon blast) The Punitive Expedition saw the advent of a lot of what we know as modern warfare beyond machine guns.

It was the first use of trucks for transporting supplies.

It was also the first use of aircraft used as reconnaissance and to carry messages back and forth.

So it kind of signaled the end of cavalry and a new era of mechanized modern warfare.

NARRATOR: Despite a spirited campaign-- at one point, the 10th Cavalry even disguised themselves as Mexican bandits-- after nearly a year in Mexico, the U.S. Army gives up the chase.

They never found Pancho Villa.

But Major Young receives high praise from General Pershing.

Young is promoted to lieutenant colonel, and Pershing puts Young on his list of officers to command future brigades during World War I. SHELLUM: He was one of the best cavalry officers in the Army at the time.

Charles Young was slated to become a brigadier general.

They couldn't have him in command of a division.

SHELLUM: If he was used in Europe the way he wanted to, he would have been commanding Black troops, but led by White officers.

White lieutenant colonels, White majors, White captains, White lieutenants.

And at the time, that was a problem for the War Department.

NARRATOR: A medical examination board found that Young had a range of health problems related to his long service in the Army.

SHELLUM: He was about 52 years old.

He'd spent a lifetime as a cavalry officer in the saddle, and he had blood in his urine.

He'd had blackwater fever, and that was working on his kidneys.

NARRATOR: But due to Young's abilities and the Army's need for the coming war in Europe, another promotion board recommends that the medical problems be waived.

SHELLUM: That recommendation went forward to Washington, so then it became a political decision.

MILLNER: President Woodrow Wilson, who was the first Southern Democrat elected to the White House since the Civil War, simply arranged it so that Charles Young was retired before he could assume that kind of position of command.

Clearly, it was a, it was a racially motivated decision, politically motivated, influenced by the racism of President Wilson and Secretary of War Baker.

NARRATOR: Young makes one last attempt to prove that he is fit to serve.

SHELLUM: He saddled up his favorite horse, Blacksmith, and decided he was going to prove his fitness by riding from his home in Wilberforce, Ohio, to the steps of the War Department in Washington, D.C. NARRATOR: Young rides nearly 500 miles over two weeks.

Despite wearing his Army uniform, he is sometimes refused service at White-owned hotels along the way.

By the time Young arrives in Washington, D.C., his ride has been covered extensively in the press, putting pressure on Secretary of War Baker to reverse his decision.

SHELLUM: And Baker essentially promised him a command if he'd go away.

Young took him to his word, and he went back to Ohio, and Baker never carried through with his promise.

NARRATOR: Young never got to serve in World War I. SHELLUM: To show the hypocrisy of the U.S. Army, they recalled him to active duty after the war, and asked him to go back to Liberia.

NARRATOR: As Young's old friend W.E.B.

DuBois asked... DUBOIS (dramatized): If Charles Young's blood pressure was too high for him to go to France, why was it not too high for him to be sent to even more arduous duty in the swamps of West Africa?

Essentially, they were sending Young back to Liberia to die.

Young loved the Army so much, he couldn't say no.

NARRATOR: Young was on a mission to the interior of Nigeria when he was struck again by blackwater fever.

He showed up at a hospital in Lagos, Nigeria, in terrible shape, and died on January 8th, 1922.

SHELLUM: Ada Young wrote letter after letter to the War Department saying that she wanted Charles Young's body brought back to the United States.

NARRATOR: A year after his death, Young's body was disinterred and brought to Washington, D.C. SHELLUM: Black citizens lined the streets to get one last look at Charles Young's casket as it rode by, trailed by a cavalryman's horse with boots in the stirrups backward, as is tradition for a cavalry commander.

NARRATOR: Charles Young was finally laid to rest with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Although never officially called "Buffalo Soldiers," Black troops served bravely in segregated regiments in World War I and World War II.

The Army's policy of racial segregation finally ended in July 1948, when President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order abolishing racial discrimination in the U.S. Armed Forces, but this did not really go into effect until after the Korean War.

Black and White soldiers did not fight in integrated units until the Vietnam War.

And it wasn't until 1972 that Dorsie Willis, the last surviving member of the Brownsville affair, was pardoned by President Nixon and given $25,000 in back pay.

By then, Willis was 87 years old.

(whinnying) Hey!

Settle down!

NARRATOR: The legacy of the Buffalo Soldiers is being kept alive in Seattle, Washington, and throughout the country.

HOWZE: My grandfather was an original Buffalo Soldier.

My father was one of the primary founders of this organization, Buffalo Soldiers of Seattle.

(reverse signal beeping) So, on a level of pride, it just allows me to continuously share the legacy that my family has developed around not only the Buffalo Soldiers of Seattle, but also just the Buffalo Soldiers in general.

This is P.J.

This is my favorite horse right here.

(chuckles) We have our marching drills, our rifling drills.

We have an hour of reading, so studying for Buffalo Soldiers' history.

♪ ♪ They fought for us.

HOWZE: Today we're going to do a couple events.

We'll be doing pony rides, a living history display, and then some mounted drills also.

The kids that know me from being an inner-urban individual, and then they see me in my cowboy gear, they're just blown away.

Lotta times they don't even recognize me.

One of the messages that I share with youth is that you have to figure out and learn where you come from.

Once I figured out and realized who my lineage was, it helped me to start to understand how I need to present myself and who I am as a man.

POWELL: The average American doesn't know much about the history of the African American soldier because they were left out.

♪ ♪ JOHNSON: Telling the story of the Buffalo Soldiers is a means of re-establishing that which was already there.

It's making history ring true.

MILLNER: When we tell the whole story, we see the ways in which Blacks in every generation, in every period of American history, have been intimate and important parts of American development.

SHELLUM: The Buffalo Soldiers paid the price for another generation of Black enlisted men and Black officers to serve in World War I and World War II.

We had the first Black brigadier general in Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. We have a Black secretary of defense today.

NARRATOR: In 1991, in Moses Williams' final resting place of Vancouver, Washington, General Colin Powell dedicated a monument to Williams and three other Medal of Honor recipients.

I have been fortunate in that for the entire time that I have been in the Army, the Army has been committed to equal opportunity, and the very serious racial barriers had been knocked down by people who came along before me.

JOHNSON: The Buffalo Soldiers had the challenge of always fighting on two fronts: fighting the enemy that the commanding officers said you're fighting, and then fighting the commanding officers, who didn't think that they were even worthy of wearing the uniform.

TAYLOR: They are very much part of what we would now call the struggle for rights.

Their very being, and sometimes their challenging of racial injustice, is reflective of their being part of that larger struggle.

NARRATOR: And that struggle continues today.

♪ ♪ GEORDAN NEWBILL: We say African American history, but we gotta get out of that-- it's American history.

You know?

It is.

(crowd cheering and applauding) ♪ ♪ MAN: ♪ Left, right, left, right ♪ ♪ Left, right, left, right ♪ ♪ Buffalo soldiers ♪ ♪ Left, right, left, right ♪ ♪ Buffalo soldiers ♪ ♪ Left, right, left, right ♪ ♪ Buffalo soldiers ♪ ♪ Buffalo soldiers ♪ ♪ Left, right, left, right ♪ ♪ Buffalo soldiers ♪ ♪ Right, left, right ♪ ♪ Explorers and mountaineers ♪ ♪ Have you been praised for your bravery ♪ ♪ As you gallantly rode your steed?

♪ ♪ Caravaning sanctuaries with your bodies ♪ ♪ There's no fear from the fire within ♪ ♪ Building trails with the rest of us to follow ♪ ♪ ♪